Has science removed all of the mystery from our world? In our lives today, science has dramatically advanced how we make sense of reality, allowing us to better understand the causes of events. We know much more today about the factors that lead to every event that happens in the world, leading to the expansion of our technology, the refinement of medicine, among other things.

Note: a version of this essay was published in the first issue of Midwest Zen

Today, it could feel like science will eventually explain every part of our life, and that in today’s world, there is no room for mystery.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, science is built on a set of assumptions about the world (that there is an objective world that exists outside of our perceptions, that phenomena in that world are orderly, and that they can be described by general laws and theories). This work, the scientific approach to the world, has allowed us to peer deeply into the fabric of the world, and to look out into the vastness of the universe.

But, even if science eventually “succeeds” – even if we believed that our scientific understanding could be complete, and that such a goal were reasonable – I would hold that even then, there will remain a mystery at the heart of reality: the mystery of existence itself.

Fundamentally, every explanation about the universe, about this life that we keep finding ourselves in, has to take existence itself for granted. Whether we explain the world based on scientific theories, or we look to religious traditions to make sense of the origin of the universe, we can never find a firm vantage point to clearly see if our explanation is really true.

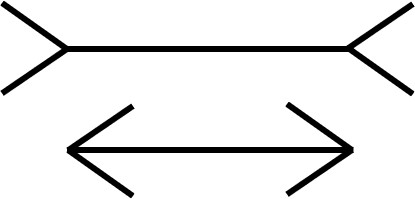

The very existence of existence, the fact that there is a world that our life plays out in, is mysterious. In science, we can trace the life of the universe back to its earliest moments with reasonably high confidence, and there are many strong theories about how the universe came into existence. Some are speculative, and our understanding of this early period is still developing, but we have at the moment a healthy range of plausible options. But, why was the universe able to come into existence in the first place? Why was it possible for something, anything to be? On this question, we have no good answers. Or, none that would not just push the fundamental question of existence back a bit further, unanswered.

We should have similar concerns about religious traditions that explain the existence of the universe through divine intervention – in the end we are left wondering, why is there a God (or gods) in the first place?

In an essay, William James captured this question very well, as he weighed the various approaches people have used to grapple with the question of being:

Not only that anything should be, but that this very thing should be, is mysterious! Philosophy stares, but brings no reasoned solution, for from nothing to being there is no logical bridge.

William James, “The Problem of Being“

Since I first read this essay, this line has stuck with me: “From nothing to being there is no logical bridge.”

While I try to acknowledge this mystery in my life, and in my meditation practice, it is not out of an effort to answer the question: I’m not looking for the “truth” about reality, in a way that would banish this mystery. The mystery of existence is perhaps something we can feel, or approach, and it may be that mystical states (a perception that we experience oneness with existence, or a relaxation of our individual ego) can help us appreciate that mystery. But, I don’t believe there is any possible way for us to perceive the source of existence. I could be wrong, but understanding why there is anything at all seems to be a fundamental limit to our existence.

And, while the fundamental question of existence is mysterious, that has not led me to reject the scientific approach. I personally still feel that the world around us is orderly and predictable. I have not felt a need to reach for magic, or miracles (in the sense of causes that operate outside of natural laws) to explain what happens in the world.

For me, this is the same way I feel about the possibility that life, and intelligent life, exists beyond our own planet. In the entirety of the universe, the number of stars around us is likely countable (that is, finite), but vast, deeply vast. The rich variety of life on Earth is supported by a single star, our sun. In our galaxy, the Milky Way, there are an estimated 100 to 400 billion stars, and that is just one galaxy. In the observable universe (what we can actually observe is limited by how far light can travel and the expansion of the universe), there may be around one hundred billion galaxies, each with hundreds of billions of potential suns for their own gardens of life.

The sheer number of stars around us, at this moment alone, is staggering, and really beyond comprehension. In all of that creation, could our planet be the only one to support life? The only one with life that has turned its gaze back to itself, and taken delight in the miracle of existence?

Maybe, but I would not bet against those odds!

However, while I have a great deal of confidence (faith) in the existence of life out in the universe beyond our own planet, I have very little faith in reports about UFO encounters, which claim that our planet is regularly visited by beings from other planets. Recently, there were a set of reports about UFOs, some of them related to releases of information from the United States military. While a UFO, or an unidentified aerial phenomenon (UAP) includes any unexplained aerial encounter, most people who are excited about them see evidence of aliens visiting Earth.

While the possibility of life on other planets is very high, from what we know now, the challenges to actually travel between stars is formidable. Unless we find some solutions that can get around limits like the speed of light, any actual travel to another star will take huge investments of time and energy. Other civilizations on other planets may have solved these problems, but the idea that they would have already found us seems pretty unlikely. Not impossible, but one of the principles of a scientific attitude is when you propose a very unlikely theory (that aliens are visiting our planet), you need exceptional evidence, and we certainly don’t have that yet. I would expect that most UFO reports are going to turn out to have rather mundane explanations (such as problems with specific cameras on military planes).

In the same sense, the heart of our existence is a mystery, but not one that necessarily opens the door for magic (unfortunately!) or other approaches to explain existence. This mystery is the foundation of our reality: a firm bedrock that patiently tolerates our efforts to turn it over, and examine it. A mystery that effortlessly dodges both scientific and mystical attempts to tame it. Each effort to break through this mystery, whether through scientific investigation or through mystical experience, leaves the foundation unmarred, unmoved.

Personally, I have found that appreciating the mystery of existence to be an important part of my own meditation practice, and I think that this quote from Carl Sagan captures my own attitude today:

For myself, I like a universe that includes much that is unknown and, at the same time, much that is knowable.

A universe in which everything is known would be static and dull …

A universe that is unknowable is no fit place for a thinking being.

Carl Sagan, “Can We Know the Universe? Reflections on a Grain of Salt”

When Sagan writes about what is unknown, he was not really referring to that which we can never know, but more to the work that is left to do for science (that part of experience that can be explained using scientific theories). But, I would also say that it applies here: there is something important about understanding that some parts of experience are fundamentally unknowable. To experience directly, to touch the mysterious, is equal parts humbling and wonderful.