What is this life that we find ourselves living? What is this place that we find ourselves in? For me, these were the kinds of the questions that brought me to meditation, and to Zen practice when I was younger. Growing up, I was not exposed to a strong religious tradition, and felt that I lacked a framework to explain the larger meaning of this life. Over the years, I have felt that my meditation practice has been an important part of how I have found my way in life, helping me to be more aware of the ways in which my own reactions to events in my life can draw out resistance, and struggle. Meditation has opened up more space in my life, to move out of the comfortable ruts of habit, to act with less defensiveness.

Today, I am somewhat grateful for not having a formal religious upbringing, as I feel that opened some space for my own explorations. And, I am still very concerned with the question: what is the nature of this reality that we find ourselves in? How can we move skillfully through the world?

Beyond my meditation practice, and Zen Buddhism in particular, science has been a critical part of my understanding of the world that we are in, and what we are (the nature of human existence). I see my meditation practice as focused on careful observation of life from the “inside,” so to speak: the world as we actually, directly experience it. Even early in a meditation practice, cultivating awareness of our lives can provide many insights, about how we may close ourselves off to others, or to how rumination can lead us to suffer.

For me, I see the scientific approach as complementary to my practice: if my focus in meditation is often to look at the direct experience of life, then the scientific approach is to look at life (the conditions that give rise to our existence as sentient beings, and the structure of that experience) from the “outside,” so to speak. The scientific approach begins from the observation that our experience is generally not random: there is a structure to our experience, and the world appears to operate according to firm, dependable principles.

Some people will call science a religion, and I can see how that is reasonable, but in my experience it is a useful tool. Science is a way of building knowledge about the world, starting from set of foundational premises, really assumptions, that are critical to the entire structure. When introducing science in psychology and neuroscience, we tell our students that science is grounded in four “canons”:

- empiricism (knowledge is built on observations of the world)

- determinism (events have orderly causes)

- parsimony (if we have two explanations for the same event, we prefer the one that is simpler, e.g. the one that explains the event with the fewest assumptions)

- testability (that our inquiry is limited to questions that can be answered using empirical observations)

Other scientists might debate the number and nature of the foundations of science, but these basic principles are the bedrock of strong science (and these specific four are ones used in a textbook that I am fond of, by Pelham & Blanton, Measuring the Weight of Smoke, and if you are interested, I’d suggest checking out this sample chapter).

Science has proven to be an exceptional system for understanding the structure of the world around us. However, science also has very strong limits (boundaries) that come from the four canons. One in particular is the focus on testability: as scientists, we are only concerned with questions that can be addressed using empirical observations (our own direct observations, or those we can make based on tools, such as thermometers to measure temperature, scales to measure weight).

For this reason, I feel that science is a critical part of making sense of the world, but I don’t see it as a religion, or a spiritual practice, as science is agnostic, or disinterested, in fundamental questions. As a scientist, I find the important questions (“What is the meaning of this life?” for instance) are unanswerable.

So, then why do I feel that science complements my practice at all?

Mainly, it is because I can see the ways in which our perceptions of the world are inherently limited by our human form, and science, especially psychology and neuroscience, have helped to reveal the nature of our limits, and their sources.

For example, consider illusions: cases where our perception (experience) does not describe the world accurately (as we would measure the world more objectively). The “blind spot” is a good example: people with normal vision often forget that each of us is blind in a small part of each of our eyes, the blind spot. You can demonstrate this for yourself (here is one online demonstration from McGill University, from a site with a number of interesting educational activities about the brain).

The blind spot exists because of a quirk of the anatomy of our eyes (and specifically the retina, the very back of our eye). The light sensitive cells in the retina gather information to send into the brain. That information travels into the brain through the optic nerve. But, the fibers that gather to form the nerve pass through the retina, creating a “hole” where there are no light-sensitive cells. (If you have ever had a photograph taken of your retina during an eye exam, you will likely have been able to see the optic disc, which is where the optic nerve is passing through the retina).

So, each person with normal vision is partially blind in each eye. And, each of us is also generally unaware of the blind spot. Our own blindness is hidden from us. However, with careful observation, we can demonstrate the existence of the blind spot, and some very interesting studies have also been done, to study how the brain fills in the blind spot with a guess as to what should be there, based on the context around that location.

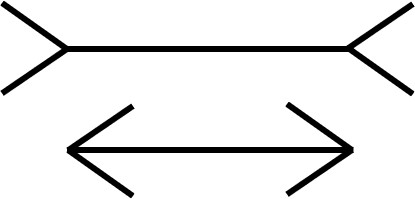

As another example, take the Müller-Lyer illusion (right). For most people, the horizontal line in the top figure appears to be longer than the horizontal line in the bottom image.

But, they are the same length! You can test this by holding up a piece of paper along each end, or try visiting this link to this illusion on The Illusion Index, for an animation that shows the length of each line, and gives more info on the illusion. The reason we experience the Müller-Lyer illusion is still a matter of debate (some have pointed out that the arrowheads at the ends of the lines function as depth cues, for instance).

Illusions such as these show that our perceptions (what we experience) can deviate strongly from the world around us (what people generally would experience, if we measured the world objectively). In many ways, this is expected, as our perceptions are not thought to be intended to report exactly what is out in the world around us. Rather, what we perceive is our best guess about the world, or a balance between our best and most useful guess.

Outside of perception, there are also fascinating cases where our understanding of our own ability to pay attention fails us. One example that I like to discuss with my students is inattentional blindness, a situation in which we are unaware that we are not attending fully to what is going on around us. The video below is based on the work of Dan Simon and his colleagues, and is an excellent demonstration (if you haven’t seen it already, that is!).

Inattentional blindness is related to selective attention, the idea that our ability to attend to what is going on around us is usually limited, and we can only focus on a few things at once. But, we are often blind to the fact that we are not processing other events or objects. And, we may miss something important, even when it feels like we are paying attention intensely!

While people may vary in how strongly they experience inattentional blindness (just as with visual illusions), it is very likely that many of us, much of the time, are blind to how much information we are filtering out all around us.

Work with perceptual illusions and “cognitive illusions,” such as inattentional blindness, have helped to demonstrate not only that our perceptions of the world can be limited in important ways, but that careful measurements of the world can show us more clearly the ways in which our experience can be distorted.

This is the first step, for me, to trying to correct for these distortions (to be more humble, for instance, that I may have missed an important event, has been a great help when the people around me disagree on what happened in a specific incident). I have found this to be a very valuable perspective for my own practice, to approach my own experience with humility.

One other area of science, and especially psychology and neuroscience, that is important for my own practice comes from studies of how our perceptions of ourselves as stable, separate beings is built. For instance, I took a moment just now to look at my right hand. I raised it up, stretched out my fingers, then clenched my fist. The feeling of ownership was very strong: this is my hand, certainly. The perception of ownership comes, almost automatically.

But is ownership of my hand really a given?

For example, in my home right now, there is a silicone replica of a hand on a nearby table. I know that this hand is false, and not a real hand.

(Don’t worry, having an extra hand lying around is quite normal in our home, living with a child who is an artist. Because, after all, who isn’t going to need an extra hand someday?)

Now, imagine that my child were to set this false, silicone hand down on my desk. Right next to my own right hand, maybe while I was distracted. And, imagine that the silicone hand and my own were both covered at the wrists, so I could not see where my arm ended, and my hand began.

Looking down, would I be confused about which was my own hand, and which was the false one? Probably not, but why? Is ownership of my hand natural, and given?

No, that does not seem to be the case. While it seems that the decision (that is a false hand, this is my hand) is easy, and effortless, in reality the decision requires active work by our brains. And one easy way to demonstrate this is with the rubber hand illusion (this piece in The Guardian has a nice description of the illusion, and some interesting work on the effects of the illusion on the brain).

To experience the illusion, I could hide my right hand under my desk, and leave the false hand in the same orientation. Then, if someone were to touch my right hand (under the desk), and the false hand, simultaneously, and in the same pattern, I might start to experience the rubber hand illusion. It would start to feel as if the false hand is actually my own. Not every person is susceptible, but for those who are (and I am one of them), it can be a very disconcerting experience.

I know (in an intellectual sense) that the false hand is not real, that it is not even made of flesh. But as I see someone touching it at the same time I feel someone touching my hand, the perception of ownership is real. It can fluctuate between shades of ghostly displacement, and something sharper, stronger feelings of “self.” This is an illusion just as much as the Müller-Lyer, where lines of equal length appear to differ in our perceptions.

While it seems to be a simple thing to say, “this is my hand, that is not,” in reality, it is much more difficult to do. The existence of the rubber hand illusion points to the fact that it really is difficult to find our body in the world, and we (our brains) weigh information from several senses (sight – seeing our hand, proprioception – feeling where our hand is positioned, and touch – feeling something contact the hand).

Where these sensations are strongly correlated (I see someone touch a hand/I feel my hand being touched), then usually, what I am seeing is my own hand. This leads to the feeling of ownership, that is part of building up a sense of myself as separate from the world around me. What it is especially important, I think, is that this sense of myself is built, not found in the world. And, it is unstable (if something as simple as the rubber hand illusion can unsettle it, momentarily).

Are these insights fundamentally different from those offered by Buddhism? Probably not (many of you can likely identify parallels or independent observations in Buddhism that offer similar insights). But for me, to be able to better understand the nature of our form and how it operates in the world has been invaluable. But, also something that I set aside in my practice, and especially in meditation.

As Shohaku Okumura advised, our intellectual understanding can be important, and we should set it aside in our meditation:

It’s really important to first have a kind of intellectual understanding about what our practice is. When we sit on the cushion, we should forget about it, and just sit. It’s the same as when we drive a car, or when we learn how to drive a car. First we have to study about the parts of the car, and how to deal with it. But when we really drive a car, we should forget about that knowledge, and just drive.

Shohaku Okumura, Mind and Zazen