Many of us come to our meditation practice with the hope that we can improve ourselves, that we can become our best self. This is a natural, normal place to begin. But, in Zen Buddhism, we often encounter teachings that ask us to examine our motivation for our practice very closely, lest it lead us to greater suffering.

Note: a version of this essay was published recently by The Tattooed Buddha

For instance, consider the First Noble truth in Buddhism, that that human life is characterized by duhkha (often translated as suffering, but dissatisfaction is closer). Steve Hagan, in “Buddhism Plain and Simple” explains that our suffering has three major sources. We cannot avoid pain (physical and mental). Change is core part of our experience (so pleasure is fleeting). And, if we identify our life with our self (our existence as a separate being, one thread of identity that traces its way from birth to death), then we can suffer greatly as we worry about when that thread will be broken.

If we do not understand the causes of duhkha, or dissatisfaction, in a deep way, then our approach to our meditation practice may just continue our attempts to avoid pain, to resist change, and to turn away from the knowledge that our lives will end someday. Instead of working towards freeing ourselves from duhkha, our practice could end up being cosmetic, something closer to spiritual plastic surgery.

And in fact, the comparison to surgery seems appropriate here. In medicine, we have made great strides in our ability to heal the body, and repair injury. But, at our local dermatologist’s office this week, I was struck by the number of advertisements for purely cosmetic treatments. Rather than focusing on treating a medical condition, or conditions such as acne, the focus felt to be on fighting against the inevitable decline of our bodies. Or, helping us meet some standard of beauty that we felt we have fallen short of.

And, this seemed like just more duhkha – any benefits we might obtain will fundamentally be unfulfilling, if we do not realize that we cannot stop aging entirely, or that there are limits to how much we can modify our bodies.

In our lifetimes, we are going to see more of these kinds of advertisements, and we will see more that reach past our external appearance to try and shape our minds as well. Even today, our ability to repair the nervous system is improving, and cochlear implants for individuals with hearing loss are a good example. More interventions are on the horizon (for individuals with vision loss, or paralysis, for example).

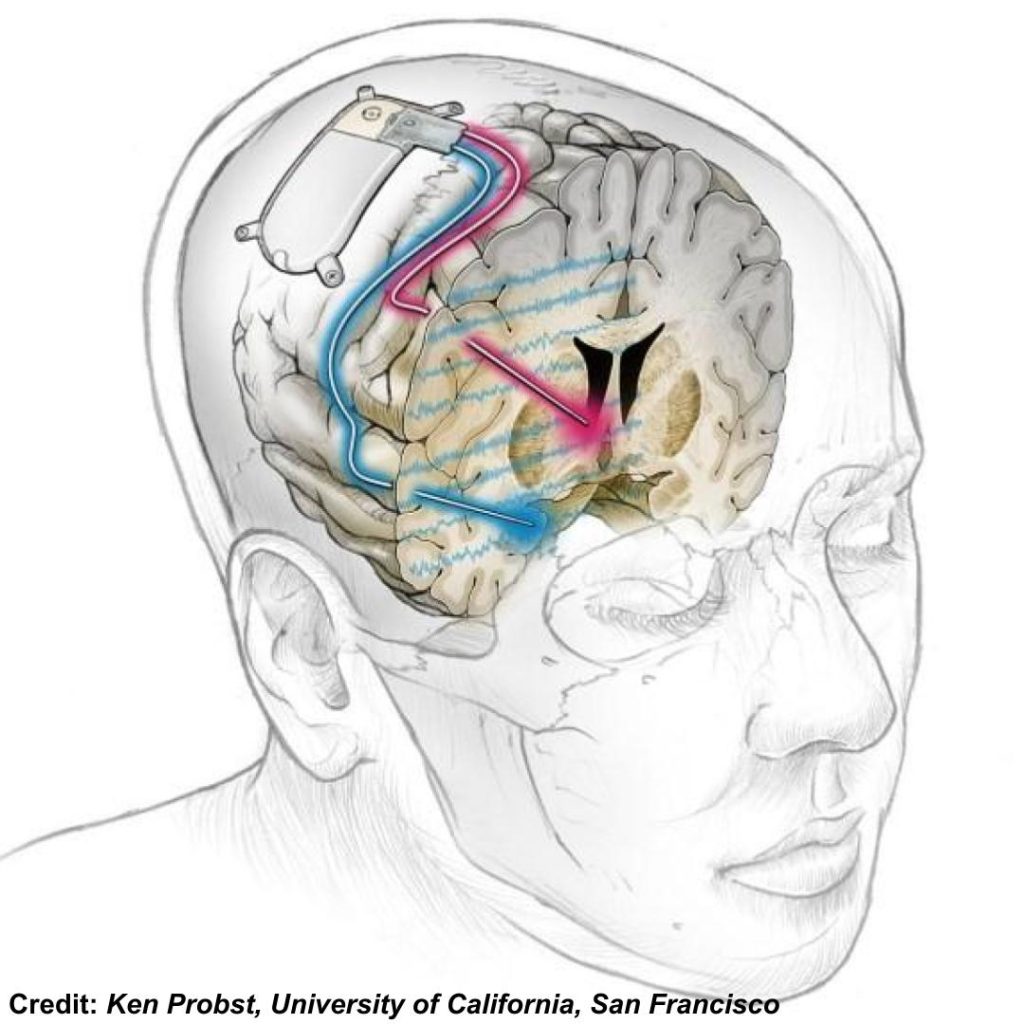

And, there is considerable promise to intervene far beyond sensation (hearing, vision) and movement (paralysis). You may have seen a story recently, about a case where direct brain stimulation was used to help a young woman who had a long history of treatment-resistant major depression (for a good summary, see this summary by Dr. Francis Collins).

This case is remarkable, and one that will be very important as we work to create new, and more effective, options for mental health treatment.

Some of these treatments will change our lives for the better, as reconstructive surgery has done. But, following closely behind that work will be those companies that want to sell us all manner of neuroscience enhancements – perhaps as a kind of cosmetic surgery for the brain.

Recently, I listened to an episode of Shankar Vedantam’s Hidden Brain, that captured this tension – our interest in using new technology to improve our daily lives, and be more effective. In the second half of the episode, Vedantam visits George Mason University, to learn about research using transcranial direct current stimulation (dTCS) to help regular people improve their ability to focus their attention after being distracted. In the piece, he describes the allure of this kind of neurostimulation in a way that seems very familiar:

… the idea of running an electrical current through my head is not exactly appealing. But the possibility that I could juggle the many demands on my time? That’s irresistible.

Shankar Vedantam, “Work 2.0: Life, Interrupted” starting at about 34:56

In recent years, many groups have been studying the effectiveness of tDCS to influence our cognition and emotion. The basic technique is quite simple and essentially uses a battery to send a very weak current through the brain.

While research like that described in the episode have shown that tDCS has some potential to improve some cognitive skills, Dr. Melissa Scheldrup (who was a graduate student at the time), expressed hesitation about using the technology casually:

I personally don’t think that tDCS should be used in somebody’s everyday life. It should be used as a tool to look at the underlying physiological process. So, I don’t think that everybody should have a helmet that has this… it’s like cheating.

Melissa Scheldrup, “Work 2.0: Life, Interrupted” starting at about 47:54

While I personally am not as worried about this technology becoming a type of cheating, I do have concerns about adopting this technology to help us be better workers. I worry that this may just be a shortcut, that stops us from looking more deeply at why we feel we need to be better workers.

But, many companies are pressing forward with technology aimed at neuroenhancement. For instance, I recently came across an article from the Huffington Post from back in 2015. The story was about a device produced by the company Thync to help us decrease anxiety using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) of the vagus nerve. The first line was interesting: “What if you could zap your brain into a state of calm or energy with only the push of a button?”

Indeed, what if we could?

Thync’s stimulator was based on at least one interesting research study (published in 2015 in Scientific Reports), but their early consumer devices never really caught on.

Today, Thync seem to be marketing some new products, like one that they call the “FeelZing” energy patch. An ad on their site promises “Energy and focus boost for 4 hours,” and “Reduced mental fatigue,” where a dose of electrical stimulation can give you a boost without needing to use caffeine or other stimulants. Images in their promotional video show a person apparently in seated meditation. The narrative appears to imply that the FeelZing gives the benefits of meditation (energy? focusing?) without needing to resort to caffeine or stimulants.

Personally, I find this work, to apply research findings to better our lives, to be very interesting. And, to also be fundamentally flawed if we use them in isolation. It feels that some of this work is focused on treating the symptoms of our dissatisfaction, rather than the root cause of the disease of suffering. To really benefit from any of these technologies, we need to look at the root of our suffering. Otherwise, we may just be leaning more heavily into duhkha.

And here, I think that some advice on Zen practice may be helpful. While there is no perfect way for us to ensure that our meditation practice is not just more duhkha, I have appreciated advice from Zen teachers such as Dainin Katagiri. Of zazen (the practice of seated meditation), Katagiri said that “Some Zen teachers tell us how helpful it is for us to do zazen… But I said just the opposite: zazen is useless” (Dainin Katagiri, “Returning to Silence”).

Meditation is useless? This may seem like a contradiction, to recommend that we pursue a useless practice. But, the important point is that when our meditation practice is motivated by what we expect to “get” out of it (the benefits), then this can be an obstacle to ending suffering.

In a similar vein, Charlotte Joko Beck advised us that the fruits of a meditation practice may not be those we expected when we first sat down:

What we get out of practice is being more awake. Being more alive. Knowing our mischievous tendencies so well that we don’t need to visit them on others. We learn that it’s never okay to yell at somebody just because we feel upset. Practice helps us realize where our life is stagnant.

Charlotte Joko Beck, “Nothing Special: Living Zen”

What I have appreciated about these approaches to Zen practice is the call to be aware, as much as we can, of when our motivations are driven by duhkha. And, to still act (to continue meditating, to continue to learn about our bodies and the brain). Katagiri pointed out to how we can work to transform our “thirsting desire” – our ambition, our craving to get what we want – into something that benefits all beings:

According to the story of Zen Master Rinzai’s life, he planted pine trees at the temple for two reasons: one was to make the scenery of the temple more beautiful, and the other was so they would be there for future generations. His activity was based on human thirsting desire, but his purpose was vast, extending in the universe. If you use thirsting desire in a selfish way it is really dangerous, but if you use thirsting desire for the benefit of others, your purpose, your hope extends far.

Dainan Katagiri, “Returning to Silence”

Our desire for pleasure, for power, and to hold off the inherent transiency of life can all lead to suffering. But, if we “know that thirsting desire is something that can be used for all sentient beings”, as Katagiri said, then we can transform that desire and through it, the world.

If we understand these points, then I think that the fruits of our meditation practice, and from our use of new technologies will lead us to our best self. And, that best self happens to be one that has let go of all of our gaining ideas.