The mystery of consciousness – how minds arise in the material world – has perplexed me for most of my adult life. This question drew me to both Zen Buddhism and neuroscience when I was in college. Still today, I believe that it is important to understand why consciousness exists – because the nature of consciousness, and of our self, can tell us a great deal about what we truly are, in the deepest sense. o, it is no surprise that I was very excited when I came across Being You by Dr. Anil Seth, a new book on the science of consciousness.

In the book, Dr. Seth presents a synthesis of current research on consciousness, with a focus on his one work (primarily in the area of perception). In the prologue, Seth begins with a description of a time when he went under general anesthesia.

Experiences of anesthesia are not exactly common (many people have likely never had a surgical procedure that requires general anesthesia. Or, they have only had one, if any). But, general anesthesia is also not exactly rare. Personally, I have been put under anesthesia twice, but not since I had my wisdom teeth removed when I was a teen.

So, given the “ordinariness” of this procedure, I was impressed with how Seth used it to tease out the problem of consciousness:

Five years ago, for the third time in my life, I ceased to exist… I returned, drowsy and disoriented but definitely there. No time had seemed to have passed… I was simply not there, a premonition of the total oblivion of death, and, in its absence of anything, a strangely comforting one.

Anil Seth, “Being You” (pages 1-2)

From this (rather unsettling) start, Seth goes on to lay out the problem of consciousness: how does our consciousness emerge from the activity of a brain? He acknowledges that many other researchers and scholars have struggled with the “hard problem” of consciousness, which he introduces with a quote from Dr. David Chalmers:

It is widely agreed that experience arises from a physical basis, but we have no good explanation of why and how it arises. Why should physical processing give rise to an inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does.

David Chalmers, “Facing up to the problem of consciousness”

This problem, a kind of philosophical koan, is one that has gripped me for as long as I can remember. As a college student, I vividly recall long walks on the unpaved roads near my home, looking across empty corn and soybean fields at the setting sun. I struggled to understand, then and now, – why do I experience this light as a rich set of colors? Why does the winter breeze feel cool? How does my subjective experience actually come from the activity of the brain?

In this book, Seth recommends that we set the hard problem aside, and to focus on what he frames as the “real problem.” The real problem frames the goals for a science of consciousness to “explain, predict, and control the phenomenological properties of consciousness” (p. 25).

While at some level, this feels like Seth is dodging the important question, I left feeling that this could be a valuable mindset to bring to consciousness research. He made an interesting comparison to early theories about life, some of which held that life required something extra, “a spark of life.”

But, a focus on describing and detailing the basic properties of life and living systems has eliminated a need for something “extra” to explain life. As Seth summarizes:

As the details [of life] became filled in – and they are still being filled in – not only did the basic mystery of “what is life” fade away, the very concept of life ramified so that “being alive” is no longer thought of as a single all-or-nothing property… Life became naturalized and all the more fascinating for having become so.

Anil Seth, Being You, p. 32

I don’t know that the consciousness research will follow a similar path, and let go of the hard problem in the end. But, I think that Seth makes a strong argument that focusing on the real problem will help consciousness research move forward. His own book gathers many of the fruits of this approach.

Is seeing believing?

As a Zen practitioner and neuroscientist, one section of the book that I found particularly compelling was how Seth looked at the contents of our conscious experience – essentially our actual subjective experiences. He focuses on our perceptions of the external world at first, and points to how our perceptions of reality are limited. The argument he uses is pretty much consistent with what I’ve written here about how our senses are limited, and misleading, and about the limits of our ability to truly experience “reality.” He argues, for example, that all of our sensory experience of the world – the sights, sounds, smells, etc. that we experience – are not really faithful representations of the world, but are our “best guesses” – in a statistical sense – about what is out there in the world.

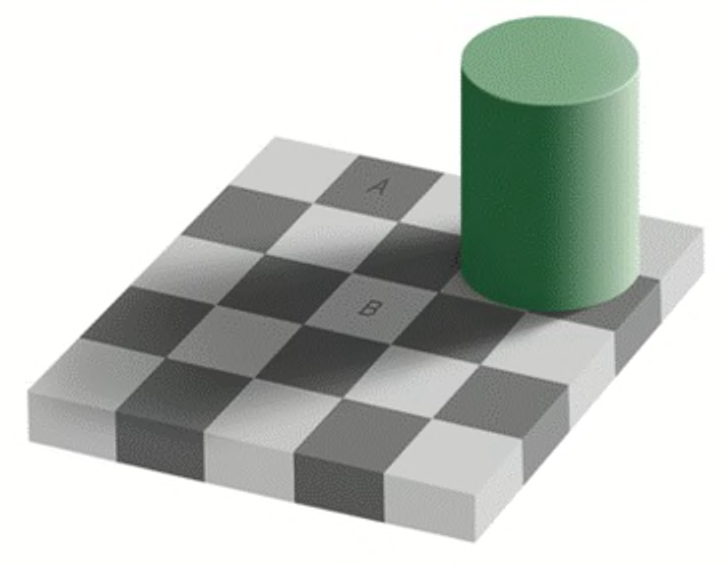

This is easily demonstrated in visual illusions, where our experience of color is not determined just by the wavelengths of light that are falling on the retina in our eyes, but also by the context. For example, in the checkerboard below, both boxes A and B really are the same color, but we perceive A as being much darker because of the surrounding context:

But, there is an important difference in emphasis in Seth’s approach, compared to how I would normally describe perception. Usually, I would say that my experience of the world (what I see, hear, taste, etc.) is a representation of the sensory data that that I am receiving. It is how my brain is representing the information coming in from my sensory nerves. I would accept that the brain is attempting to correct for missing information, or context (as in the visual illusion above), so of course we should not trust our perceptions to be direct measurements of the world. The goal of the brain is to produce a useful representation.

But, I would normally accept that what I am experiencing is the incoming sensory information itself. That view, the one I held, assumes that perception is as a process where our senses provide a window onto the world. That window is not fully transparent, certainly. The window controls what information gets through, and transforms or distorts it.

But, Seth goes farther, I think, and in an important way. He argues that our experiences of the world, the contents of our consciousness, is not the sensory information itself. Seth points out that the brain has no direct link to “reality” – it is stuck inside the skull. And the information that the brain receives from the senses is only partial, and often imprecise. So, at each moment the brain must make its best guess about what is out there, in the world, to try to explain the (unreliable, incomplete) sensory signals that are received.

In this view, what we actually experience – the feeling of texture, the color of the sky – is not the sensory information itself. Instead, we experience the predictions that the brain is making, the brain’s best guess about what is out in the world. The sensory information itself, in this view, is mainly used to verify if our guess (a prediction) about the world is true. For this reason, Seth describes our experience of the external world as a controlled hallucination, one where the brain is creating a set of predictions (also referred to as “top-down” – that is, from the brain) that are compared to incoming sensory information (also referred to as “bottom-up” – that is, from the sensory organs).

It seems as though the world is revealed directly to our conscious minds through our sensory organs. With this mindset, it is natural to think of perception as a process of bottom-up feature detection – a “reading” of the world around us. But what we actually perceive is a top-down, inside-out neuronal fantasy that is reined in by reality, not a transparent window onto whatever that reality may be.

Anil Seth, Being You, p. 88

Seth describes this as a controlled hallucination, because he argues that the brain is always making these kinds of predictions. And, when the process of making “top-down” predictions becomes disconnected from those sensory signals, that is when we would start to experience real hallucinations.

But, and for me this was a critical point, Seth points out that the line between hallucination and accurate perception is not a sharp one, but a matter of degree. The brain is constantly making predictions, and what we experience are the predictions. When they are tied to the sensory data, then we would say that a person is accurately perceiving the world. But in both cases, they make up the contents of our conscious experience.

You could even say that we’re all hallucinating all of the time. It’s just that when we agree about our hallucinations, that’s what we call reality.

Anil Seth, Being You, p. 92

Under this view, hallucinogenic drugs may decrease the impact of sensory data, allowing top-down predictions (our best guesses) overwhelm our experience. While Seth does not give much attention to other states, this could also explain some of the properties of dreaming. Or even the kinds of hallucinations that can be common during intensive meditation (makyō):

The makyō I’ve experienced include the sense that my hands in the zazen mudra were huge (a persistent one early on), faces in the wall I sat facing (a particularly beautiful Avalokiteshvara), and the piercing song of a bird coming from the far side of a lake perhaps three miles away.

Dōshō Port, “Is Awakening (Kenshō) a Hallucination (Makyō)?”

Are we more or less than beasts? Than machines?

I found Being You to be a worthwhile read, and there were many other sections that I found personally relevant (as a Zen practitioner, and as a neuroscientist). I would recommend the book to others, because it was one of those books that showed me the world from a new perspective.

But, there were other sections of the book that I would have liked to see Seth develop further. One of these areas was Seth’s presentation of his overall theory of consciousness, and our sense of self – what he calls the “beast machine” theory. After arguing that our perceptions of the world are fundamentally controlled hallucinations, Seth makes a similar case about emotions and interoception (sensations from the body).

Around this point, Seth introduces a theory of consciousness, and the self, that is grounded very strongly in our status as living being, and in our biological drive to stay alive. We can easily take life for granted, but in reality, keeping even one cell in our body functioning is a delicate dance. How much more difficult when that body has trillions of cells? Seth argues that this drive, to live, is at the core of our brain function:

Evolutionarily speaking, brains are not “for” rational thinking, linguistic communication, or even for perceiving the world. The most fundamental reason any organism has a brain – or any kind of nervous system – is to help it stay alive, through making sure its physiological essential variables remain within the tight ranges compatible with its continued survival.

Anil Seth, Being You, p. 196

Working from this premise, Seth develops the “beast machine” theory of consciousness (and self), which he states as “Our conscious experiences of the world around us, and of ourselves within it, happen with, and because of our living bodies.” (p. 181)

I cannot do justice to the argument here, certainly, but I feel that in this area, he has drawn too narrow of a foundation. Staying alive is a key goal for any living being, and to be certain, it is not an easy process. At every moment, our bodies must work to push back against entropy.

But, is that our only goal, evolutionarily speaking?

Perhaps, but many of the behaviors we engage in are only very weakly related to our physiological survival. Some motivations fit very well: consider the drive to eat, drink, find shelter (all of which help keep our bodies in an optimal range). But what of our motivations for exploration, sex, and parental care. What of the drives that support our social communities? These motivations might somehow serve physiological goals (keeping our body alive), but the direct benefit to our own physiological state seems tenuous. Seth draws one explanation for exploration (as a way of better predicting what you’ll need to do in the future to protect yourself), but I felt even that link was thin.

To flesh out Seth’s theory of consciousness and self, I would have appreciated seeing him integrate more of what we know about other systems in the brain, besides perception. For instance, while there is some attention to decision-making (in the chapter, “Degrees of Freedom”), this part of the book could be developed further. For the interested reader, I would recommend Dr. A. David Redish’s book, The Mind Within the Brain for a good overview of decision-making systems in the brain (full disclosure: Dave was my PhD adviser, so I’m not entirely objective!). For those interested in a Buddhist perspective on the mind (focusing on cognitive and evolutionary psychology), I would also recommend Robert Wright’s excellent book, Why Buddhism is True.

And, while these concerns might seem technical, or trivial, I think they do matter a great deal. Or could, some day.

If we believe that consciousness is intimately tied to our status as living creatures, then we will have concerns about extending any moral protections to non-living beings. And at the moment, that makes perfect sense. But, what about in the future?

Seth uses the popular examples of the android Ava from the movie Ex Machina, and the androids in the series Westworld (both of examples of humans treating their creations quite terribly). By centering his theory on our status as living things, Seth seems unwilling to accept that these (fictional) creatures could be conscious. And he wonders about these kinds of cases: “Will we feel that these new agencies are actually conscious, as well as actually intelligent – even when we know that they are nothing more than lines of computer code?” (p. 269-70).

Seth does state clearly at other points in the text that he is claiming that he believes machine consciousness to be impossible. But, the tone of the book seems skeptical of the potential for machine consciousness, and I worry about that. If you read Being You, I would ask that you look at that part of the book very carefully. If you walk away from this book holding on to a theory that will make it harder for us to recognize machine consciousness, if it ever emerges.

If you end up believing that the take-away message of Ex Machina and Westworld is that we should be worried about being too nice to androids, I think you missed the point.

As work in artificial intelligence proceeds, there is no guarantee if and when one of these robots/androids/programs would become conscious, but if we don’t admit that it is possible, then I do worry that we will unintentionally (callously?) be introducing new suffering into the world.

And, if we are truly committed to freeing all sentient beings from duhkha, we should at least be ready to pay attention to the androids.