… instead of thinking in terms of movement toward something new and shiny and different, let’s try thinking of spiritual practice as a process of remembering that which we already know.

Mark Frank, That Which We Already Know, p. 30

What does it really mean for us to follow a spiritual path? What is the nature of our effort – are we looking to find some kind of insight or experience? Or, are we working towards some other goal?

In Buddhist practice, we are encouraged to look closely at our motivation, to notice what is fueling our efforts, And, we often find that we are striving towards some goal, looking for something outside of our self that might fulfill us, that could ease our suffering. But, this type of seeking is an error – a type of craving that can up prolonging our suffering.

But, even if we are not striving to get something, that does not mean that are not working towards something. We might frame this as a change of view, that our goal is not to get something, but to see the world in a different way.

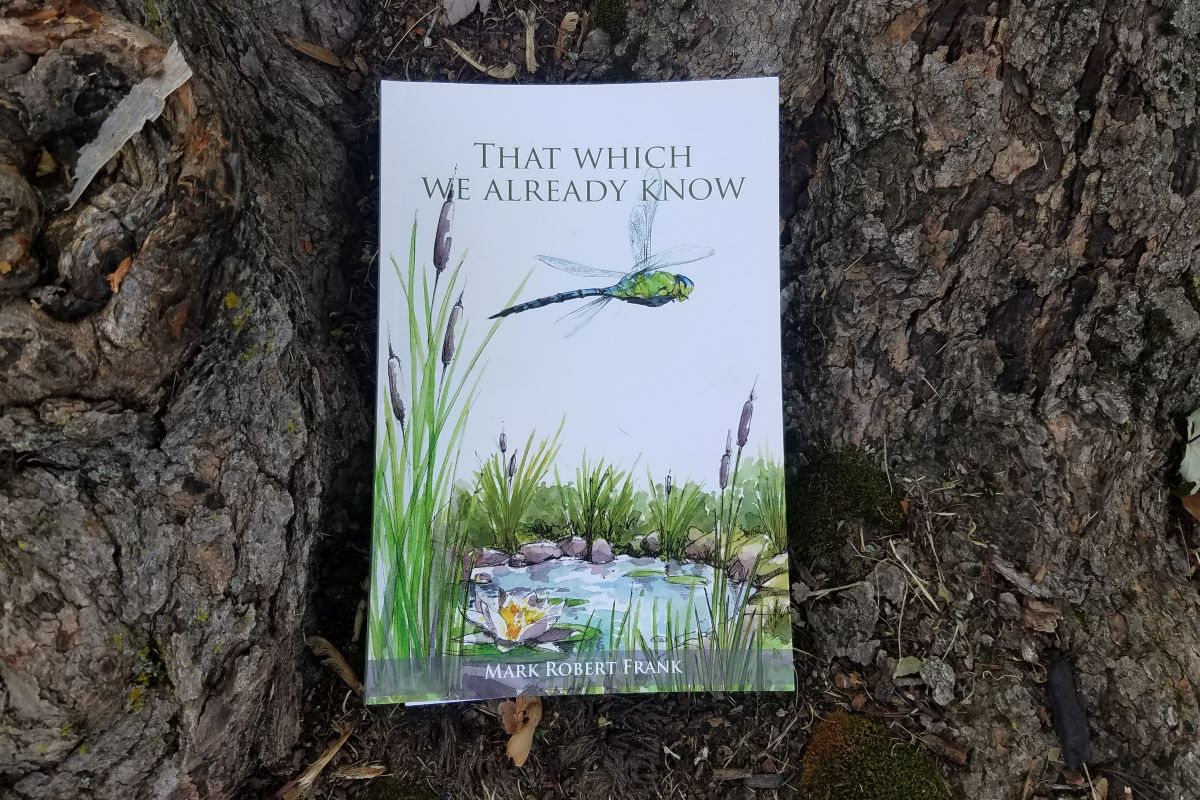

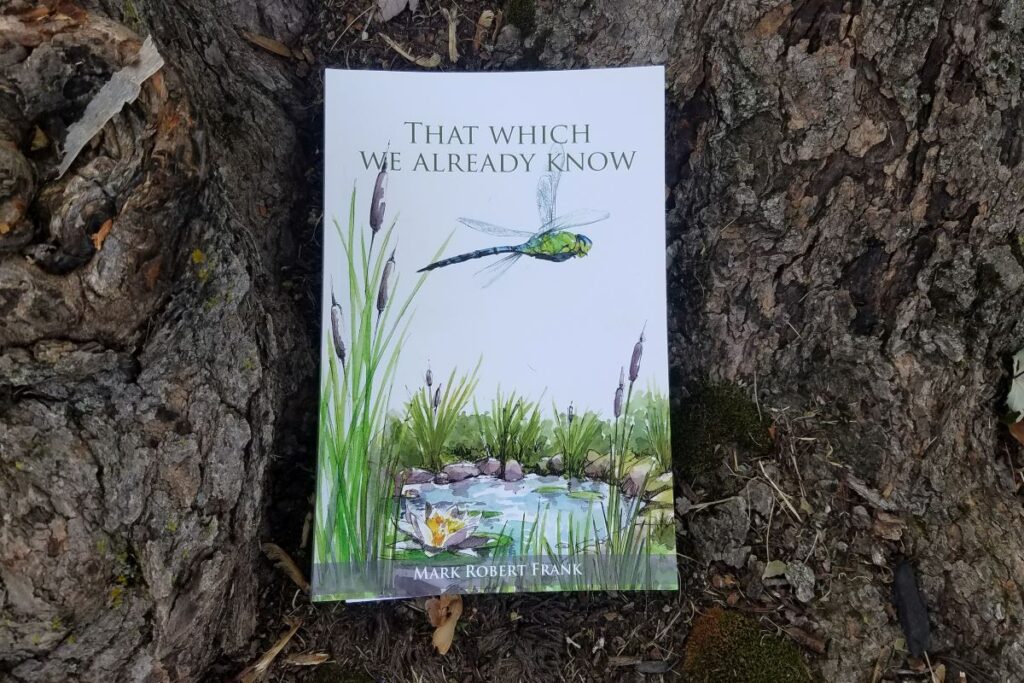

Recently, I had a chance to read That Which We Already Know, a new book written by a friend, Mark Frank. Mr. Frank is a Zen practitioner, and has written over the years about spirituality and his experiences, including on his blog, Heartland Contemplative. His book focuses on this question: what is it that we are working to realize, in our spiritual practice?

That Which We Already Know is structured as a memoir centered on Frank’s childhood, and richly infused with insights from his Zen practice. He writes beautifully about the time he spent exploring the “Nursery” – a patch of wilderness near his childhood home that he presents as a kind of mini-Eden. The affection he has for that place is clear and touching, and reminded me of my own childhood, growing up in the farmland of rural Illinois.

Frank uses stories about growing up immersed in nature to illustrate his argument: that the goal of our spiritual practice, which Buddhists often name as awakening, is in fact a state that we experienced as children. His premise, and the title of the book, is that awakening is something we already know, and many of our deepest spiritual practices are helping us reconnect with that state.

An important part of Frank’s argument is that in childhood, before we develop the ability to strictly see ourselves as individual, separated from the world, we experience directly a sense of connection and wholeness. As we grow and mature, we develop a strong sense of self-awareness – the feeling that there is a me existing separate you and the rest of the world.

Do you recall such days lived without any sense of separation, with trust and acceptance, with mind and body seamlessly integrated one with the other and together with all things? … This is the freedom of children and the wisest among us, and everything else that resides in the natural world – the freedom to be precisely what we are and nothing we are not …

Children don’t simply know this freedom; they embody it. Ironically, our developing self-awareness brings this freedom into view just as it begins to disappear, like sunlight creating a rainbow in the mist even as it boils that mist away.

Frank, p. 9-10

Looking at the development of self-awareness, Frank draws an interesting parallel to the Christian story of Adam and Eve, framing our normal development as a kind of recapitulation of that first fall from grace. As we grow and mature, our sense of self develops, and we “fall” out of this state of grace into our ordinary, deluded state. Of Eve and Adam’s lack of shame (of their nakedness) before consuming the fruit of knowledge, Frank proposes that perhaps the lack of self-awareness, of being a person separate from the world, was the source of their innocence:

… we might think of this nakedness in metaphorical terms. They’d not yet become clothed with any ideas of separate selfhood. It wasn’t just that they were unaware that they’d done something wrong. They were unaware of being separate beings in the first place.

Frank, p. 14

Reading the book, I thought a great deal about Frank’s premise, the argument that spiritual awakening might share some similarities to states we experienced as children. And, I realized that I have often taken for granted that I see spiritual practice (study, meditation, prayer) as focused to realize something that I did not know. I found that I have assumed, without really thinking much about it, that I came into existence as a deluded being, and my practice was focused on letting go of some of my own false views. Perhaps the difference is subtle, but it was one that I appreciated once I saw it.

Reading Frank’s descriptions of his own childhood, which do make up some of the evidence for his argument, I did struggle to see childhood as an idyllic time when we live without a self (at least not once we are old enough to go off and explore the wildness). In the end, this did not end up resonating with my own experience. I actually cannot say that I have very many concrete memories of being a child – I reach and find only vivid little fragments here and there. And, some of the drier facts that I remember about childhood. I enjoyed my childhood, as I remember it, and I value my experiences. But I do not feel deeply nostalgic about the actual experience of being a child. I don’t remember experiencing the kinds of deep experiences that Frank finds in his own past. And, I don’t know that my spiritual practice is focused on reminding me specifically of what I knew as a child.

Perhaps the gap, between my own recollections and the vision that Frank describes, has something to do with the times and places we each grew up in. Frank mentions the shadow that the Vietnam War and the draft cast over his own childhood. At that time, a real, palpable loss of innocence loomed as one grew towards adulthood. In the early 1980s, I did not have a similar experience, and I don’t remember having any specific concerns about becoming an adult.

I do wonder, though, about the children growing up today. A time marked by the strains of the COVID-19 pandemic, and deep polarization. And I wonder whose childhood – Frank’s or my own – would resonate most deeply with my own daughters.

But, even though the specific image of childhood as a time of wisdom, and awakening, did not resonate with me, the larger argument is one that I found interesting, and compelling. To understand that the innocence of children is a kind of wisdom, and that we can let go of some of the rigid views that cut us off from that wisdom – these were some of the key treasures I took from this book, and I am grateful to Frank for sharing his experiences.

And, while I don’t personally look back to my own childhood and see a state of wholeness and wisdom, I do find myself here and now as a single, limited being. A person that emerged at some hazy point in memory from a place of stillness. To take a moment to look back to what came before, to try to touch the stillness that our life emerges from, has been an important part of my own practice, and I appreciated very much the reminders I found in this book.

Where there is meaningful religious practice, there is stillness. And where there is stillness, there is the potential for transformational human experience.

Frank, p. 142