It feels today that public debates (or rather arguments) have greatly intensified, over reproductive rights (especially abortion), racial justice, and LGBTQ+ rights (and especially for trans persons). At the heart, these conversations are grounded in morality – what are we free to do, and how should we treat one another? What do we owe to one another?

As we see how polarized these struggles have become, it is easy to be discouraged, and feel that there is no way for us to agree on these basic, and important, questions. We might start to feel that there is no “right” way to do morality.

Looking out from this particular moment, we can see that so many behaviors have been moralized in one way or another. What is condemned in one time and place may be ignored, or even praised, in another. While we can identify some common principles across time and cultures (a respect for fairness, for instance), it has seemed to me that we could not establish that one particular moral system is good, or better than another.

And, as a scientist, I have also felt that morality is really outside of the reach of the scientific method. I often tell my students that in science, and psychology is no exception, our focus is on problems that we can approach empirically – questions that we can answer by making careful measurements in the world, using methods that exist today.

In classes, I often give them an example of a problem that is beyond the reach of science, such as “What is the meaning of life?” This is an important question, perhaps the most important one that any person will grapple with. And, the ways that we answer this question can shape the entire course of our lives.

But, as a psychologist, I cannot answer this question – there are no measurements I could make that would firmly establish the “true” meaning of life. I can ask other questions: how do people develop their sense of meaning in their lives? How do different systems (religious, agnostic, atheistic, etc.) impact people’s well-being, or their behaviors? How do important life events impact our beliefs about the meaning of life? The list of interesting questions that we can address is enormous.

But, I don’t think that I can answer that first question: What is the meaning of life? The question itself stands outside of psychology, and science.

And, in my conversations with my students, I have always included morality along with those other questions that are outside of science. Why do people help one another? Why do we judge, or hurt others? Certainly, these are the kinds of questions about morality that science has looked at closely. And, we have learned a great deal through their study. But, the fundamental questions: what is right, and what is wrong? – these are not questions that we can address through empirical means.

Or, at least I thought so, until I read a new book, Changing How We Choose, by David Redish1. Dr. Redish is a neuroscientist whose work has focused in recent years on decision-making, and understanding how the brain allows us to choose the best actions for each situation. And, how those decisions can go awry (think of addiction, for instance). For anyone interested in learning more about the neuroscience of decision-making, and how decisions can go “wrong,” I would highly recommend his earlier book, The Mind within the Brain.

In his new book, Redish makes the case that across all of our various moral systems, we can see not only human universals in morality (reaching towards fairness, loyalty, avoiding harm, etc.), but that we can identify a goal towards which any moral system is striving.

The key, in Redish’s argument, is that morality is a set of tools, or a social technology, so to speak, that allows humans to cooperate with one another. In this framework, morality creates and maintains the conditions in which humans can work together and cooperate. At the very core, morality imbues cooperation with value, and supports cooperative behaviors while restraining selfish behaviors.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

In building his case for cooperation as the key concern of morality, one Redish’s key frames comes from game theory. Game theory focuses on the mathematics of situations where people are in competition with one another, and where the best choice that you can make as an individual depends on what other people do. One classic example is the prisoner’s dilemma, which considers a case where two people are suspected of a crime. I personally like this version, from the Encyclopedia Britannica:

“Two prisoners are accused of a crime. If one confesses and the other does not, the one who confesses will be released immediately and the other will spend 20 years in prison. If neither confesses, each will be held only a few months. If both confess, they will each be jailed 15 years”

(Britannica)

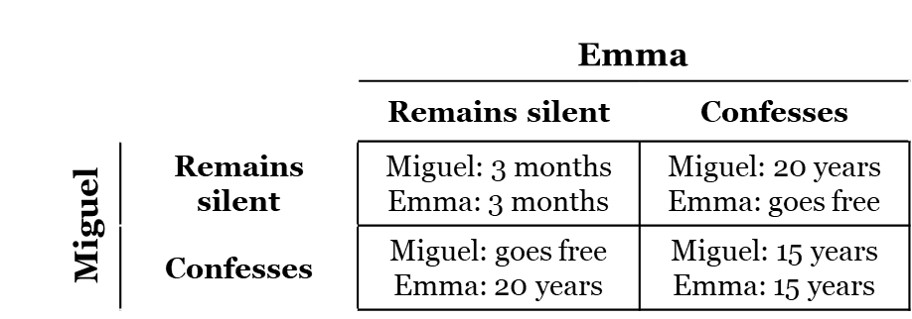

Imagine that we have two people, Emma and Miguel, who are suspected to have committed a serious crime. If both of them do not confess, they will spend three months in prison, and otherwise the penalties will be the same as those in the case above. We can then represent the possible outcomes with a table:

Based on this way of looking at the problem, we can consider what Miguel and Emma should do, if they want to avoid spending time in prison. But, while we will consider this situation amorally (without worrying about what they should do in a moral sense), I do want to acknowledge that it feels wrong to treat serious crimes as games – if Emma and Miguel are guilty of a serious crime, we would generally hold that they should confess, right?

If we do approach this situation just from the self-interest of Emma and Miguel, it is clear from the table above that the best choice for Emma and Miguel is to remain silent. In this case, they only spend a few months in prison. And, if they can work together, this might be a feasible “strategy.” But, the prisoner’s dilemma includes a wrinkle: Emma and Miguel each must make their decision alone:

“[The suspects] cannot communicate with one another. Given that neither prisoner knows whether the other has confessed, it is in the self-interest of each to confess himself. Paradoxically, when each prisoner pursues his self-interest, both end up worse off than they would have been had they acted otherwise”

(Britannica)

This is an important point: if Miguel and Emma each do not know what the other chooses, and they are only in this situation one time, then the best strategy for them as individuals is different from the best strategy for them as a group.

Take Emma, for example, as she considers her options: if Miguel were to confess, then her best option is to confess as well (spending 5 less years in prison). And, if Miguel were to remain silent, her best option is still to confess (and spend no time at all in prison).

Apart from our moral concerns about responsibility for our actions (if a person really did commit a serious crime), this kind of analysis can feel unsettling – as if we are endorsing cold, selfish behavior.

The Assurance Game

A fundamental part of Redish’s argument is that for humans, most of our interactions are not competitive in ways that match the prisoner’s dilemma. Or, at least, they do not have to be competitive in this way.

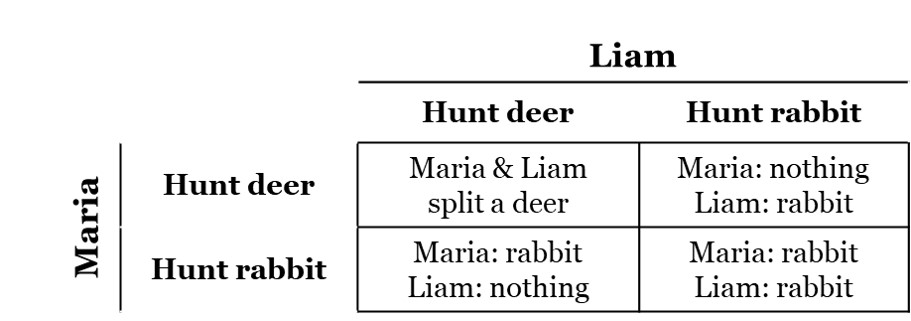

In many cases, if humans can cooperate effectively, then the group of cooperating people is more successful than each person could be individually. To illustrate this, he uses the assurance game. Like the prisoner’s dilemma, the assurance game is a case where we will all be better off if we work together. But, in the assurance game, you can decide not to cooperate without suffering the kinds of risks (of loss, or punishment) that happen in the prisoner’s dilemma. Redish uses an example that was introduced by Rousseau in his work, A Discourse on Inequality, where Rousseau considers hunters working together to take down a deer:

“If it was a matter of hunting a deer, everyone well realized that he must remain faithful to his post; but if a hare happened to pass within reach of one of them, we cannot doubt that he would have gone off in pursuit of it without scruple.”

(Rousseau)

While today, hunting deer is usually an individual activity, it was not always so. So, we can imagine two people, Maria and Liam, who have a chance to work together to hunt for deer (without all of the benefits of modern hunting equipment). In this case, we can say that they will be more likely to succeed if they work together than if they hunt for a deer separately. If they were to hunt for rabbits alone, they are more likely to be successful, but also will get less food. Like the prisoner’s dilemma, we can represent the potential outcomes as a table, like this:

I personally do not have a great deal of experience with game theory, and for a time, the important difference between the assurance game and the prisoner’s dilemma escaped me. But, Redish points out that the key is that the assurance game rewards cooperation, without also rewarding people who act only in their self-interest.

In the prisoner’s dilemma, if Emma cannot communicate with Miguel, and has no idea what he will choose, her best choice may be to confess. And, the same is true for Miguel.

In the assurance game, Maria is better off hunting rabbits if Liam decides to hunt rabbits. But, she is not better off if Liam will hunt for deer with her. In fact, she is much worse off, because the benefit from a deer is much greater than that of a rabbit.

It is an oversimplification of Redish’s argument, and of the research fields that he draws on, but a key insight is that for humans who can live and cooperate together, in many cases the benefits of cooperation (to the individuals participating in that society) are much greater than a person could earn if they lived entirely on their own (if that was even possible). And, Redish sees that morality is focused on creating the conditions where more and more of our interactions are actually assurance games (where cooperation is nurtured).

“… what humans call morality is a set of mechanisms that help us turn our interactions into an assurance game and to find our way into the cooperate-cooperate corner of that assurance game, where we can reap the benefits of its non-zero-sum nature and make things better for all of us, both as a community and as individuals. Fundamentally, humans have evolved to work together. Morality is a set of tools that make us better team players”

(Redish, p. 265)

Redish presents morality as a set of tools, a kind of technology, that helps humans create and succeed in assurance games. The tools of morality are built out of our social interactions, but they also depend on a set of systems in the brain. Redish points to emotions such as shame and guilt. Guilt is commonly felt when a person realizes that they have violated a norm or rule for their community, while shame often comes when that violation is known by the community. “Guilt is a recognition of the offense, but shame is the recognition that one is part of a team and has let the team down.” (Redish, p. 64).

We might very well worry that in some times and places, shame and guilt are overused to restrict the behavior of some people in a society. But, would a society be better (work better) if every person had no ability to feel any guilt or shame?

I would guess not. But, this does not mean that guilt and shame are necessarily appropriate. We can consider how these emotions are used with any moral system, and ask if they are aligned with the goals of supporting cooperation. If we find they are being used oppressively, to restrict one group’s behavior or opportunities, then it does become possible to judge that moral system as less effective than it could be.

What does it mean for our Zen practice?

As we think of the implications of this work, I think that any religious person should consider how these arguments impact their own religious practice. As a Zen practitioner, I feel that it is important to think carefully about how we apply these lessons of the science of morality.

One part that I appreciate in Redish’s proposal for a scientific study of morality is how well it overlaps with the ways morality is understood in Buddhism and Zen. For example, in his commentary on Dogen’s Shishobo, Shohaku Okumura writes:

“Bodhisattva practice is not the way of self-sacrifice. The goal of our practice is to find a way we and other beings can live together without causing suffering to each other. This is the middle way between pursuing only one’s own interests and sacrificing oneself.”

(Okumura, p. 12)

And, while I appreciate the overlap between Redish’s proposal for a scientific understanding of morality, I don’t think that this view will replace our religious or spiritual frameworks. Redish has an interesting chapter on religion, in which he sees morality as the core of religion, writing:

“… quite literally, religion is about morality. It defines groups through shared beliefs, shared rituals, and shared sacrifice. It defines structures within those rules so that everyone has a part to play. It embodies rules that limit intragroup conflict.”

(Redish, p. 238)

I certainly won’t argue that religions (even Buddhism) are not concerned with morality. And, they do includes these elements that he describes. But, fundamentally, from the perspective of our lived experience, religion is not about morality. Or, at least is should not fundamentally be about morality. It should be about the “why” of it. Why do we exist, and what is the meaning of it all?

Religions, and other systems of belief, answer that question in different ways. Specific moral systems can follow from those answers. But, morality is not at the core of religion. A science of morality may be very useful as we consider the strengths and weaknesses of our moral systems. It may give us easier ways to have conversations across traditions and cultures with very different moral systems. But, it will not, or should not, supplant those traditions.

For comparison, consider the science of nutrition, in which I can see many parallels to the argument that Redish advances. Nutrition, as a science, focuses on the ways that our diet supports our bodies. Not every diet (in the sense of what we eat, rather than in the sense of restricting what we eat) is equally beneficial for our health.

And, we can see the traditional cuisines of a culture as a set of tools that support the nutrition of its people. Just as with morality, there is likely no single “correct” way to eat – there is no such thing as the one and only perfect nutrition. But, we can judge different patterns of eating against the effects of those diets on health. And, there are certainly failures when it comes to nutrition.

For example, once when I was a teenager, I spent about a week at a camp that was held on a military base in Ohio. Meals were available in the mess hall, but generally required getting up early, and this was a serious obstacle to me at that time. So, I had come prepared for the week with a large stash of Pop Tarts. And, for at least two full days, I do not think I consumed anything except Pop Tarts, water, and probably many soft drinks. I’m not sure how well I could tolerate that diet today, but even then, I do remember feeling very ill one night. It was quite some time before I ate another Pop Tart.

Like morality, there may not be a single, perfect cuisine to support nutrition. And, there certainly ones that we can identify as bad, like much of the highly processed foods that flood our stores and fight for our attention today.

But also, eating is not about nutrition. Not from our own position, the one that we actually live. To eat for nutrition is to let your cuisine die. Eating is moment of deep connection, a humbling acknowledgement of our interconnection to the entire world. Meals are also very social, a time when we come together in community. To reduce cuisine to nutrition – at the level of our own motivation – is a terrible mistake. The same is true, I think, for morality. The science of morality may give us new insights into the core, or most fundamental parts, of our ethical systems. It may help us also recognize what parts are superfluous, what we can discard. Maybe.

“We all do better when we all do better.”

Paul Wellstone

Redish opens his book with this quote by the late Senator from Minnesota, Paul Wellstone, who died tragically in a plane crash when I was in graduate school at the University of Minnesota. Senator Wellstone was a wonderful example of the kind of person that we would all be better for emulating. Buddhism and Redish’s science of morality would agree on that point, and I hope that the conversations that this new book stimulates will help us all work together to reach for this goal. We will all be better if we do.

1Full disclosure! Dr. David Redish was my graduate adviser for my Ph.D., and a colleague and friend today.

Works cited

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, December 23). Prisoner’s dilemma. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/prisoners-dilemma

Okumura, S. (2005, September). “The 28th Chapter of Shobogenzo: Bodaisatta-Shishobo The Bodhisattva’s Four Embracing Actions – Lecture 5” Dharma Eye, 16. https://www.sotozen.com/eng/dharma/pdf/16e.pdf

Redish, A. D. (2022). Changing How We Choose: The New Science of Morality. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Rousseau J.-J. & Cranston M. (1984). A Discourse on Inequality. Penguin Books.